Table of Contents

ToggleThe 90% Dilemma

The European Union is on the brink of enshrining a landmark climate goal for 2040 – a 90% net reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels. This “target crunch” comes to a head in late 2025 (with an EU Climate Law amendment due and a UN 2035 pledge needed by September). Hitting 90% by 2040 is incredibly ambitious, essentially putting the EU on track for near-net-zero by 2050. The big question: how to get there. Will Europe lean more on carbon capture and storage (CCUS) to mop up industrial emissions? Will it bank on carbon dioxide removal (CDR) – sucking CO₂ from air or enhancing land sinks – to offset what it can’t cut? Or will a massive deployment of green hydrogen replace fossil fuels in heavy sectors, obviating some need for capture or offsets? Each pathway has winners and losers, and Europe’s policy decisions in the next year will signal which horse it’s betting on.

“It will feel less like a single big change and more like a steady redesign of how we live and work,” said Neil Fried, Senior Vice President, EcoATMB2B, in response to Industry Examiner. “You’ll see more EVs and chargers, heating powered by renewables instead of gas, and more emphasis on recycling and reuse.”

The Balancing Act

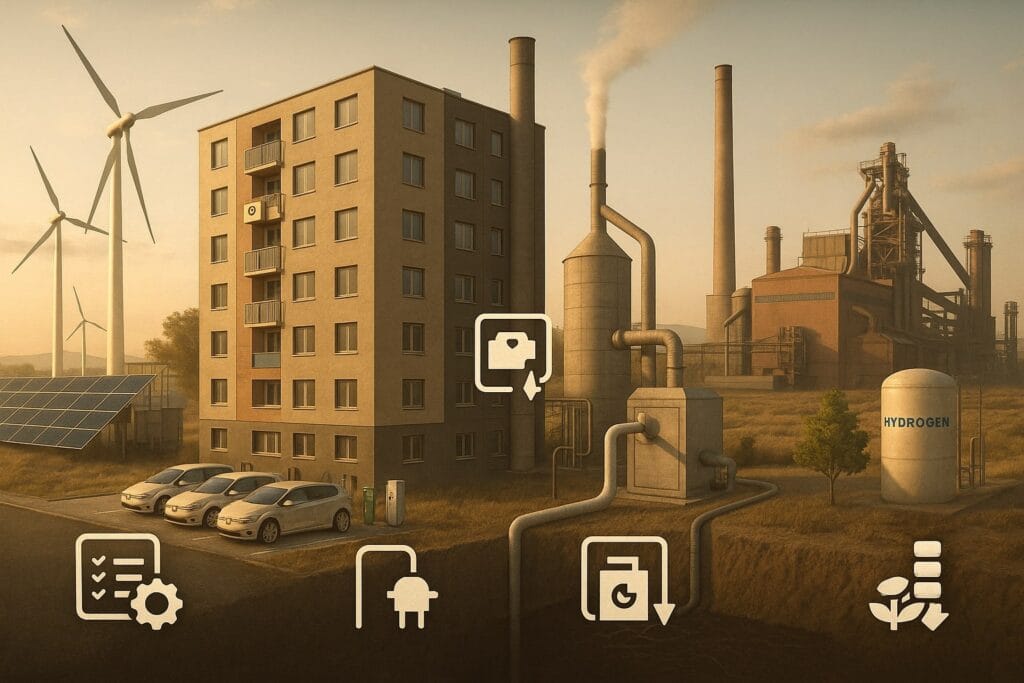

In reality, the EU will need all of the above – efficiency, renewables, electrification, plus some CCUS, some hydrogen, some removals. But the mix is under debate. The European Commission’s impact assessment lays out different scenarios: one scenario (S1) achieves 90% mainly through direct emissions cuts, minimal reliance on removals; another (S3) leans heavily on green hydrogen and CCS to decarbonize industry and transport, plus engineered removals to handle residual emissions. A third “LIFE” scenario emphasizes demand reductions and circular economy, thus needing less hydrogen and CDR.

“Cut at source: (1) swap fossil power for renewables and grid upgrades; (2) electrify end-uses with EVs and heat pumps; (3) efficiency everywhere (buildings, motors, processes). Where capture is needed: cement and lime (process CO2 you can’t avoid), parts of steel and refining/chemicals, and some waste-to-energy plants. What removals are for: the leftovers—dispersed or hard-to-abate emissions and some legacy CO2—once the big, direct cuts are done.” said Stephen Mayer, Director, Carbon Blue Solutions Limited LLC, in response to Industry Examiner.

The crux: all scenarios that hit ~90% require rapid scale-up of green hydrogen and CCS “in sufficient quantities” alongside clean power, according to the Commission’s analysis. In numbers, hydrogen use may need to reach 55–95 million tons of oil equivalent (Mtoe) by 2040 (several-fold higher than today), and CO₂ capture on the order of 200–400 Mt per year by 2040. For perspective, Europe currently captures only a few million tons CO₂ annually and produces a mere 0.5 GW worth of green hydrogen (electrolyzer capacity) as of 2022. Getting to the needed scale would mean exponential growth – the EU would require a 150% annual growth rate in hydrogen output (versus ~23% today) to hit its own REPowerEU hydrogen targets, for example. Similarly, announced CCS projects are ramping up – 119 new projects were announced in Europe in 2023 (+61% from 2022) – but many are still proposals.

CCUS: Necessary Evil or Climate Saviour?

Carbon capture, utilization and storage has long been contentious in Europe. Critics dub it a fossil fuel lifeline; proponents call it indispensable for industries like cement and chemicals where process emissions are otherwise unavoidable. The Commission’s scenarios reflect this tension. In a high-ambition case, fossil and bioenergy CCS might store 100+ MtCO₂ by 2040, plus additional BECCS (bioenergy with CCS) and DACCS (direct air capture with storage) contributing tens of Mt. Analyses suggest that without CCS, Europe cannot decarbonize heavy industry by 2040 – one study found without deploying capture, EU industrial emissions would actually rise to ~240 Mt by 2040 due to remaining processes. With CCS focused on industry (steel, cement, chemicals), those emissions can be slashed toward net-zero. Indeed, cement is seen as inevitably requiring CCS for deep cuts, since making clinker releases CO₂ from limestone chemistry. The question is scale and prioritization: do we reserve CO₂ transport and storage capacity primarily for industry’s needs, or also use it for power plants and CDR? If power generators or DAC projects compete for storage, it could strain pipeline and storage build-out. Some experts warn “if CCS is not exclusively prioritized for industry but also used for fossil power or CDR, competition over CO₂ storage could emerge.” This implies policymakers might “ring-fence” CCS mainly for industrial emitters to ensure decarbonization of steel and cement, rather than prolong fossil power generation.

“Carbon capture and storage is simply catching CO₂ at the source and locking it away underground,” said Neil Fried. “It helps most with cement, steel, and chemicals. The risks are cost and the temptation to delay real cuts.”

Hydrogen: How Much is Too Much?

“Using less energy shrinks the size of the hydrogen and CCS build we need—insulation and heat pumps, recycling aluminium, better transit and freight all cut the bill,” said Stephen Mayer.

Green hydrogen – made from renewable electricity – is central to EU decarbonization plans, envisioned to replace coal and gas in steelmaking, refining, shipping fuel, and as backup power. But producing and importing the required volumes is a colossal task. By 2040, the high end scenario foresees 95 Mtoe of hydrogen use – roughly 2,700 TWh energy equivalent. The lion’s share of this hydrogen would go not to direct heating, but to make e-fuels and feedstocks for sectors like aviation or chemicals. However, Europe faces constraints: limited cheap renewable electricity for electrolyzers, infrastructure delays in building hydrogen pipelines and import terminals, and uncertainty over imports. Draft EU joint scenarios show heavy reliance on hydrogen imports post-2030, potentially from North Africa or the Middle East. But those come with geopolitical and sustainability questions (will exporting countries also need that green energy at home? What if suppliers aren’t stable?). As the Commission bluntly states, current hydrogen deployment is “far too slow” – water electrolysis capacity in 2022 was a mere 0.3% of total hydrogen production. To meet even the 2030 targets (10 million tons domestic + 10 Mt imported), the EU needs to vastly accelerate.

Interestingly, a scenario focusing on efficiency (the LIFE scenario) found that circular economy measures and lifestyle changes could cut final energy demand ~20% and reduce hydrogen needs by 15 Mtoe in 2040.

“Near-term: scale heat-pump and retrofit programs with simple rebates and tight efficiency standards,” Stephen Mayer told Industry Examiner.

In fact, EU advisors note that demand-side and high-renewables pathways produce less than half the hydrogen in 2050 compared to tech-heavy pathways. This highlights a strategic choice: invest in reducing demand (through recycling, transit, diet shifts, etc.), and one can trim the exorbitant hydrogen build-out required. Conversely, a failure to moderate consumption means Europe must bet big on H₂ and accept the associated costs and uncertainties (sourcing enough electrolyzers, securing imports, etc.).

Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR): The Backstop or Loophole?

CDR vs CCS, in brief: CDR removes CO₂ from air or land and stores it durably (forests/peatlands; DAC/BECCS). CCS captures CO₂ before it leaves a stack. Use CDR for residuals and legacy drawdown—never as a crutch to avoid straightforward cuts, said Stephen Mayer.

The 2040 target debate has also brought CDR into the spotlight. The Commission proposed that after 2035, the EU could use international carbon credits for up to 3% of 1990 emissions toward the target. That equates to ~140 MtCO₂ in offsets allowed. This is controversial – some see it as an “escape valve” that could reduce domestic action, while others argue it’s a pragmatic way to handle residual emissions from aviation, agriculture, etc. Additionally, the EU is developing a Carbon Removal Certification Framework (CRCF) and considering integrating domestic CDR into the EU ETS carbon market post-2030. Even a modest integration of removals could “catalyze large-scale demand for European CDR,” notes one analysis. Potentially, power plant operators or industries could buy removal credits (from, say, a DAC plant or reforestation project) to neutralize their last few percent of emissions.

Who wins if CDR gains traction? Likely new carbon removal companies and forestry stakeholders. Europe might see a wave of DAC startups (Climeworks and others) scaling up to deliver millions of tons of removal for the ETS or voluntary markets. Farmers and foresters could benefit if soil carbon and reforestation credits are recognized. However, the Commission’s stance is that separate explicit targets for reductions vs. removals are not set in this proposal, to some criticism. Climate scientists have urged clearer distinction so that removals don’t mask insufficient emissions cuts. Still, given the difficulty of zeroing out sectors like aviation by 2040, some CDR looks inevitable to hit net −90%. The inclusion of up to 140 Mt via Article 6 offsets implies a sizable new market for high-quality removals in the late 2030s. It’s noteworthy that Germany and Sweden are already investing in permanent CDR (like DACCS) – Germany plans to import credits for national goals, and Sweden signed deals to buy DAC-based CO₂ removals. So a subset of EU countries and companies could spearhead a CDR boom, potentially making engineered carbon removal a “winner” sector by 2030.

So, Who “Wins”? In the race to 2040:

- Green Hydrogen stands to win big in investment terms. Electrolyzer manufacturers, renewable developers, and industrial gas firms could see a bonanza as Europe pours billions into hydrogen. If the hydrogen economy scales as targeted, by 2030s the EU may have created entire new hydrogen supply chains – benefitting technology providers and countries with ample renewables. However, if constraints persist, hydrogen might underdeliver, forcing reliance on more CCS and imports.

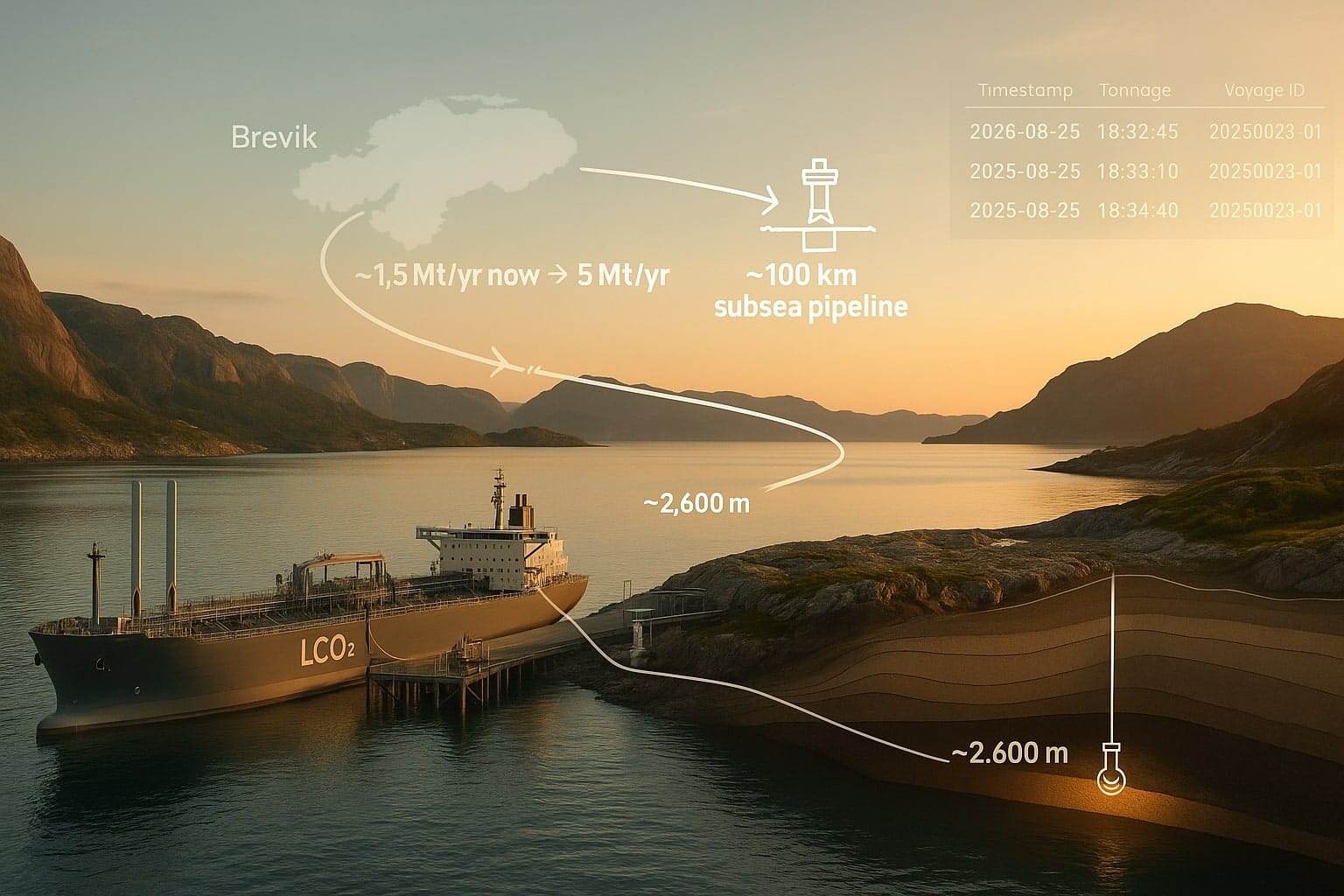

- CCUS could win as the pragmatic bridge for industries. Oil & gas companies in Europe (and North Sea countries like Norway) are positioning to provide CO₂ transport and storage services – Norway’s Northern Lights project, for example, will take captured CO₂ from across Europe and inject it under the seabed. A robust CCS push means those firms and heavy industry emitters (who invest in capture equipment) become key players in meeting the target. One report envisions 111 MtCO₂ of CCS in 2040 in a high scenario – a huge scale-up that would make CCS an entrenched part of Europe’s infrastructure (with pipelines, storage hubs, etc.). The climate trade-off is that CCS might prolong some fossil use (gas power with CCS, blue hydrogen from methane). A study noted “more CCS means less hydrogen demand but a potential carbon lock-in” risk, meaning if Europe leans too heavily on CCS, it could under-invest in cleaner alternatives and risk getting stuck with costly capture on fossil assets.

- CDR and offsets emerge as the dark horse. If innovations make direct air capture cheap, or if nature-based removals are scaled, CDR could swoop in to cover the last few percent – effectively “winning” by necessity, as purely cutting emissions to 90% may prove too slow or expensive. The Commission’s willingness to allow some offsets is a boon to projects developing “permanent” CDR like DACCS and biochar. We may see a new class of climate-tech companies in Europe monetizing atmospheric CO₂ removal at scale, supported by policy (the CRCF, national tenders, etc.). That said, nobody expects CDR to cover more than a small fraction by 2040 – it’s more a safety net than a primary tool, given current costs. High-quality removals are still costly (hundreds of euros per ton), so if they “win,” it likely means Europe fell short in other areas and had to pay the price.

2040 Target Crunch Outcome

In all likelihood, no single solution “wins” outright – Europe’s climate strategy will be an “all-fronts” effort. But decisions made in the coming year will indicate emphasis. A policy package favoring massive electrolyzer deployment, green steel subsidies, and hydrogen pipelines will signal that Hydrogen is the chosen winner for industry and heavy transport decarbonization. Conversely, if the EU doubles down on CO₂ storage – for example, by setting CCS targets or funding CO₂ hubs – that boosts CCUS as the workhorse for cutting emissions. And any formal adoption of removal credits in EU markets will give a green light for the nascent CDR industry to scale up.

The EU’s own Scientific Advisory Board warned against over-reliance on removals and urged separate targets for emission cuts vs. CDR. That suggests the smartest course is to maximize direct reductions (via electrification, hydrogen, and some CCS) and treat removals as a limited supplement. Ultimately, Europe’s winners will be those who can deliver actual decarbonization on a tight timeline. Steelmakers that adopt hydrogen direct reduction, cement firms that install CCS, utilities that build renewables and grid storage – these actors will thrive in a policy environment geared toward 90% cuts. If policy instead is weak and bets on future offsets, the real winner might be inertia – and the loser would be the climate. Given the urgency, expect the EU to push on all fronts, but the mix – CCUS vs. hydrogen vs. CDR – will be watched closely as the 2040 blueprint crystallizes in the next 12-18 months.