Denmark is turning a depleted oilfield in the North Sea into what could be the European Union’s first fully operational offshore CO₂ storage site. The plan is bold: start by injecting 400,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide a year from the middle of 2026, then scale up to as much as 8 million tonnes annually by 2030.

For a country of fewer than 6 million people, that is a striking shift in how the North Sea is used. For Europe, the Greensand Future project is a test of whether carbon capture and storage (CCS) can move from powerpoint slides to steel and rock at the speed required by climate targets.

It is also a test of something more uncomfortable: whether the same companies that spent decades extracting hydrocarbons can be trusted to run the continent’s new carbon waste-disposal system.

Table of Contents

ToggleA depleted oilfield gets a second life

Greensand Future sits 1.8 kilometres beneath the seabed in the Nini West field, part of the Siri area of the Danish North Sea. Once a conventional offshore oil project, it is now being repurposed as a geological vault, operated by INEOS Energy and partners including Wintershall Dea and Denmark’s state-owned Nordsøfonden.

The project did not appear overnight. In March 2023, the Greensand consortium carried out what it calls the world’s first full cross-border offshore CCS value chain: CO₂ captured at an INEOS chemical plant in Antwerp was liquefied, shipped to Denmark and injected into the Nini West reservoir. About 4,100 tonnes were stored over seven batches, monitored using new subsurface surveillance tools to track the plume underground.

That pilot paved the way for a final investment decision in December 2024 on “Greensand Future”, the first commercial phase. Storage operations are scheduled to ramp up from the middle of 2026, with an initial capacity of 0.4 million tonnes per year and a planned expansion up to 4–8 million tonnes annually by 2030.

Alongside the reservoir itself, the project is putting in place the hardware of a new industry:

- A CO₂ transit terminal under construction at Port Esbjerg, designed as a gateway for captured CO₂ arriving by ship.

- Specialised ships to move liquefied CO₂ from emitters around northwest Europe to Danish storage sites, including a new class of offshore CO₂ carriers developed with Royal Wagenborg.

If the timetable holds, Greensand will not only be Denmark’s first large-scale CO₂ storage site. It is on track to become the EU’s first fully operational offshore CO₂ storage facility explicitly designed to mitigate climate change, rather than to boost oil recovery.

The symbolism is powerful: a basin that helped fuel Europe’s fossil economy becoming a place where the same carbon is supposed to disappear.

Denmark’s climate arithmetic – and its CCS gap

Behind the engineering lies a political imperative. Denmark has enshrined a target to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 70% by 2030 compared with 1990 levels, one of the most ambitious goals in Europe.

Progress has been rapid but not quite fast enough. By the government’s own estimates, Denmark is on track for a 68% reduction by 2030, leaving a gap of roughly 1.5 million tonnes of CO₂-equivalent cuts still to find.

CCS is central to the plan to close that gap. The country has set a goal of about 3.2 million tonnes per year of captured and stored CO₂ by 2030, largely from hard-to-abate sectors such as cement and waste-to-energy. Projects already in the pipeline include:

- Aalborg Portland’s ACCSION project, aiming to capture 1.5 million tonnes per year of CO₂ from Denmark’s only cement plant from 2029, with EU Innovation Fund support.

- Ørsted’s Kalundborg CO₂ Hub, which plans to capture 430,000 tonnes of biogenic CO₂ annually from two biomass plants from 2026 and ship it to Norway’s Northern Lights project for storage under the North Sea.

To help bankroll these projects, Copenhagen has created a DKK 28.7bn (about US$4.2bn) CCS fund that will award long-term contracts to developers who bid for volumes and prices per tonne of captured and stored CO₂.

Yet even with generous support, Denmark’s timeline is tight. Analysts interviewed by local thinktanks warn that storage sites may not be ready at the scale required by 2030, and that costs must be low enough to compete with other decarbonisation options.

This is where Greensand matters. It offers the prospect not only of domestic storage, but of turning Denmark into a regional CO₂ sink. Geological surveys suggest the country’s subsoil could eventually hold the equivalent of 400–700 years of Danish emissions.

If that potential is confirmed, the country could store CO₂ not only from its own industries but from neighbouring Germany, Sweden, Poland and beyond – effectively exporting storage capacity as a new service industry.

Europe’s CCS push – and the 50-million-tonne target

Greensand is also a piece of a much larger puzzle. The EU has now formally acknowledged that, even with aggressive deployment of renewables, hydrogen and energy efficiency, it will need large-scale CCS to hit its climate goals.

In February 2024, the European Commission published an Industrial Carbon Management Strategy alongside a recommendation to cut net EU greenhouse gas emissions by 90% by 2040 compared with 1990.

The numbers behind that strategy are stark:

- The EU expects to need the capacity to capture at least 50 million tonnes of CO₂ a year by 2030, rising to about 280 million tonnes by 2040 and up to 450 million tonnes by 2050.

- The Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA) makes the 50-million-tonne 2030 storage capacity target legally binding, and explicitly frames it as a responsibility for oil and gas producers.

In May 2025, Brussels went further, issuing a decision that assigns individual storage obligations to 44 oil and gas companies, proportionate to their historic production between 2020 and 2023. These firms – ranging from supermajors to regional players – must help provide the geological storage that European emitters will rely on.

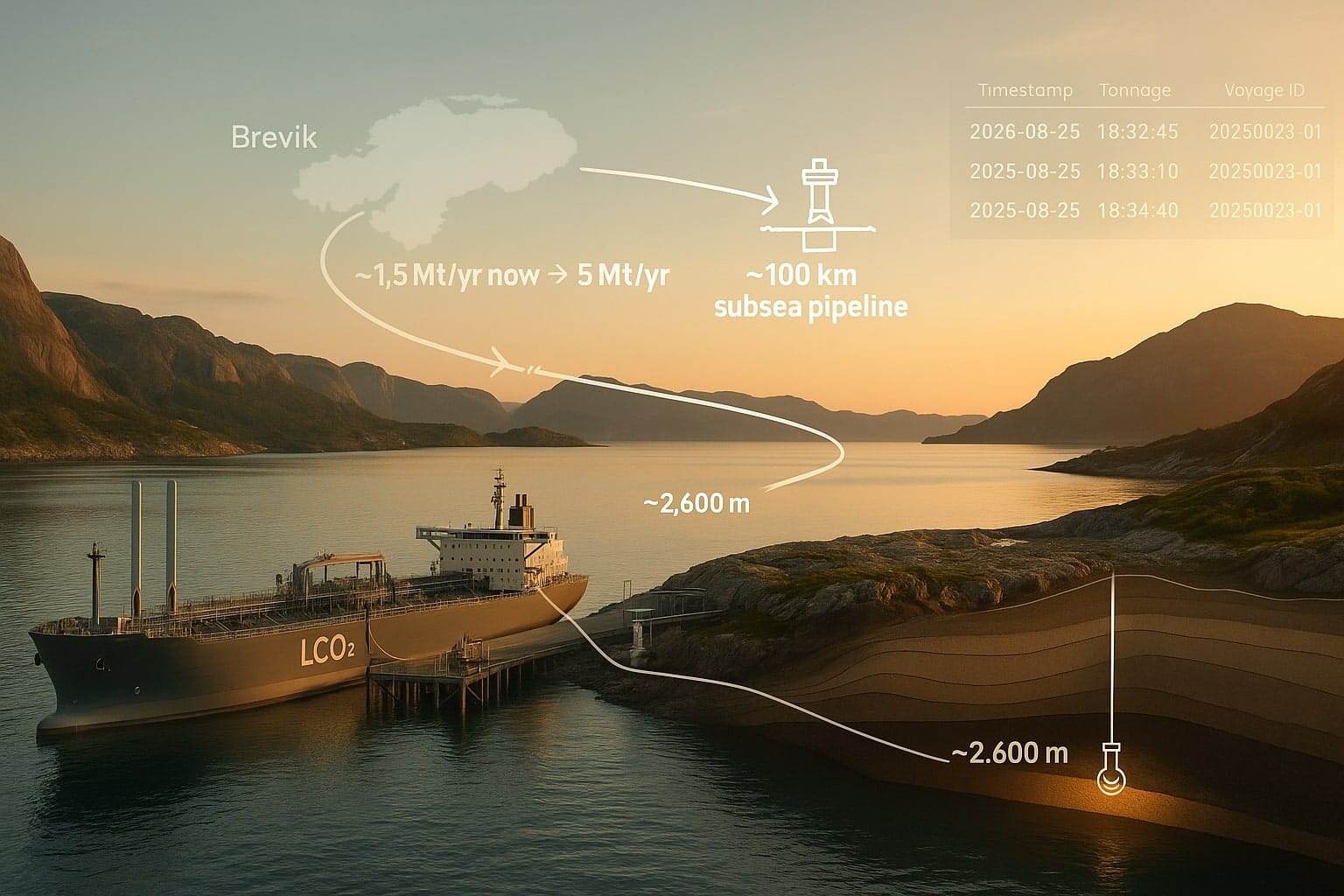

The North Sea is at the heart of that strategy. Norway’s Northern Lights project, part of the state-backed Longship initiative, has already begun injecting CO₂ into a subsea reservoir 2.6km under the seabed, with an initial capacity of 1.5 million tonnes a year and a planned expansion to at least 5 million tonnes.

The Netherlands’ Porthos project, due to start operations in 2026, will store CO₂ from Rotterdam’s industries in depleted gas fields under the North Sea.

According to a 2025 survey by industry group IOGP Europe, Greensand is just one of a growing list of European CO₂ storage projects: its own capacity trajectory is 0.4 million tonnes per year at start-up in 2026, rising to 8 million tonnes by 2030 as the Nini West field is fully repurposed.

Put together, these projects sketch out a vision of the North Sea as a shared carbon sink, linked by pipelines and shipping routes that move CO₂ across borders much as oil and gas once flowed in the other direction.

The scale problem: 8 million tonnes vs 37.8 billion

This is where the optimism meets the numbers.

In 2024, global energy-related CO₂ emissions hit a record 37.8 billion tonnes, according to the International Energy Agency – a 0.8% increase on the previous year, driven by surging energy demand and record heat.

Against that backdrop:

- Greensand’s full build-out of up to 8 million tonnes per year is roughly 0.02% of current global energy-related emissions.

- Even the EU’s legally binding target of 50 million tonnes per year of injection capacity by 2030 represents only about 0.13% of current global emissions.

Supporters argue that these percentages miss the point. CCS is not meant to mop up all emissions; rather, it is supposed to tackle specific “hard-to-abate” sectors such as cement, steel, chemicals and some waste-to-energy plants that are difficult to decarbonise with renewables alone.

But scale still matters. The Global CCS Institute counts 50 commercial CCS projects now operating worldwide, 44 under construction and more than 500 in development, as governments and companies aim to reach a combined capture capacity of 1 billion tonnes a year by 2030.

Greensand’s 8-million-tonne ambition is material in that context. Yet even if the project hits its target, Europe would still need dozens of Greensand-sized sites, plus onshore storage, to get anywhere near its 2040 capture and storage goals.

Who pays for burying carbon?

CCS is capital-intensive and, so far, heavily dependent on public support.

Norway’s Longship project, which underpins Northern Lights, is backed by roughly US$3.4bn over ten years, including about US$2.2bn in state subsidies.

In Denmark, the CCS Fund offers long-term contracts for difference that guarantee developers a price per tonne of captured and stored CO₂, de-risking what would otherwise be a highly uncertain revenue stream.

Critics point to the UK as a warning sign. An analysis by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis estimates that more than £50bn in subsidies has already been earmarked for UK CCS projects that collectively deliver only about 8% of the country’s 2050 CCS target, with as much as three-quarters of those subsidies effectively paid by consumers through levies on their energy bills.

The economic question for Greensand and its peers is whether the combination of EU carbon prices, storage fees, innovation grants and national subsidies can create a business model that survives beyond the current wave of public money.

At present, most CCS projects in Europe rely on some mix of:

- EU Innovation Fund grants, financed by revenues from the Emissions Trading System;

- National CCS tenders and contracts for difference, which guarantee financial returns over 10–20 years;

- Corporate decarbonisation commitments, particularly from companies that see CCS as a way to preserve industrial assets rather than shut them down.

That may be enough to get a first wave of storage sites built. Whether it is enough to support the hundreds of projects implied by the EU’s 2040 and 2050 targets is far less clear.

“Necessary, but only in some places”: the critics’ case

The backlash against CCS is not new, but Greensand has brought the debate into sharper focus.

Environmental groups in Denmark and across Europe warn that betting heavily on CCS risks delaying cheaper and more straightforward solutions such as energy efficiency, electrification and renewables. Greenpeace Denmark’s climate policy lead, Helene Hagel, has argued that CCS may make sense for a narrow group of sectors where emissions are genuinely hard to avoid, but becomes problematic when “almost every sector” starts seeing it as a way to keep burning fossil fuels instead of cutting emissions.

The concerns are threefold:

- Lock-in risk

CCS attached to fossil-fuel infrastructure can extend the life of assets that might otherwise be phased out. In the worst case, critics argue, this could lock countries into high-emissions pathways that are simply masked by partial capture. - Opportunity cost

State support for CCS comes from finite public budgets. Danish NGOs have questioned whether billions in support for capture and storage would deliver more emissions cuts if spent on electrifying heat, upgrading grids or accelerating building retrofits instead. - Uncertainties around “negative emissions”

Projects that combine biomass with CCS (so-called BECCS) are touted as a way to generate net-negative emissions. But the true climate benefit depends on full lifecycle accounting – including land-use change, supply chains and the permanence of storage. Danish analysts have warned that the climate benefits of capturing CO₂ at biomass plants remain uncertain and should not be treated as guaranteed.

Defenders of CCS counter that the physics of cement, steel and some chemicals simply make it impossible to reach net zero without capturing and storing process emissions. The European Commission’s own modelling assumes hundreds of millions of tonnes of captured CO₂ a year in 2040 and 2050, even after aggressive deployment of renewables and efficiency.

From that perspective, projects like Greensand are not a luxury but a necessity – provided they are tightly targeted and regulated.

Safety, leakage fears and the North Sea’s geology

Public anxiety about CO₂ storage often centres on leakage: what if the carbon seeps back out?

Geologists note that the reservoirs being targeted in the North Sea have already stored hydrocarbons for millions of years under thick caprock layers. The same formations that kept oil and gas in place are, in principle, well suited to storing injected CO₂.

Before approving Greensand’s move to commercial phase, the independent assurance firm DNV certified the first CO₂ storage site for the project, reviewing the reservoir, wells and monitoring plans.

The pilot injections in 2023 were tracked using new monitoring technology designed to map the movement of CO₂ underground and detect any anomalies. According to the consortium, the data showed the injected carbon remaining where it was supposed to be, with no sign of leakage.

Still, the Global CCS Institute notes that the industry is in its infancy: 50 operating projects and a few dozen under construction is a thin data set compared with the trillions of tonnes of CO₂ that may ultimately need managing over the century.

If anything were to go wrong in a high-profile project like Greensand, the reputational damage to CCS – and to Denmark’s broader climate strategy – could be severe.

A North Sea carbon network takes shape

Greensand is not the only Danish storage project in play.

- Bifrost, led by TotalEnergies and Nordsøfonden, aims to use the depleted Harald gas fields to store 3 million tonnes of CO₂ a year by 2030, rising to a potential 16 million tonnes after expansion.

- Greenstore, an onshore project in the Gassum area, could eventually hold up to 5 million tonnes a year.

- Other licences, including Ruby and Norne, target onshore saline aquifers and could together provide tens of millions of tonnes of capacity.

Beyond Denmark, the IOGP Europe map lists a growing roster of offshore storage projects around the North Sea and the broader European continental shelf, many backed by EU Innovation Fund support or designated as Projects of Common Interest.

Overlay this with the EU’s Industrial Carbon Management Strategy and the picture becomes clearer: policymakers are not merely dabbling in CCS. They are trying to build an integrated CO₂ transport and storage market, with:

- Cross-border shipping and pipeline networks;

- Standardised storage permits and monitoring rules;

- Obligations on oil and gas companies to turn depleted fields into storage assets.

If successful, the North Sea could become a shared piece of decarbonisation infrastructure – a kind of negative-emissions utility serving multiple countries and industries.

What success would really look like

It is tempting to treat Greensand’s story as a neat narrative arc: from oil to climate solution. Reality will be messier.

By 2030, a realistic definition of success for Denmark and the EU might look like this:

- Greensand and several other Danish sites operating safely at or near their planned capacities.

- A functioning market in storage services, with cross-border CO₂ flows from industrial clusters in Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands and Poland.

- Measurable, independently verified reductions in emissions from specific sectors – cement, chemicals, waste – that would have been extremely difficult to decarbonise otherwise.

- Clear rules that limit CCS to those sectors, rather than allowing it to become a blanket licence for continued fossil fuel use.

Even then, CCS will be a supporting actor, not the star. At 8 million tonnes a year, Greensand’s contribution barely registers against global emissions of nearly 38 billion tonnes, or even Europe’s own share.

Its real significance lies elsewhere. If Denmark can show that offshore storage can be deployed quickly, safely and at tolerable cost – and that it can be integrated with strong policies on renewables, electrification and efficiency – it will provide a template that others can adapt.

If, on the other hand, Greensand fails to scale, suffers delays or becomes a symbol of public anger over costs and fossil fuel lock-in, it will reinforce the arguments of those who say CCS is a distraction from the real work of cutting emissions.

For now, the Nini West field stands as a physical expression of a broader choice. Europe has decided it cannot meet its climate targets without burying at least some of its carbon. The question is whether projects like Greensand will become the backbone of a credible decarbonisation strategy – or an expensive detour on the way to a cleaner energy system.