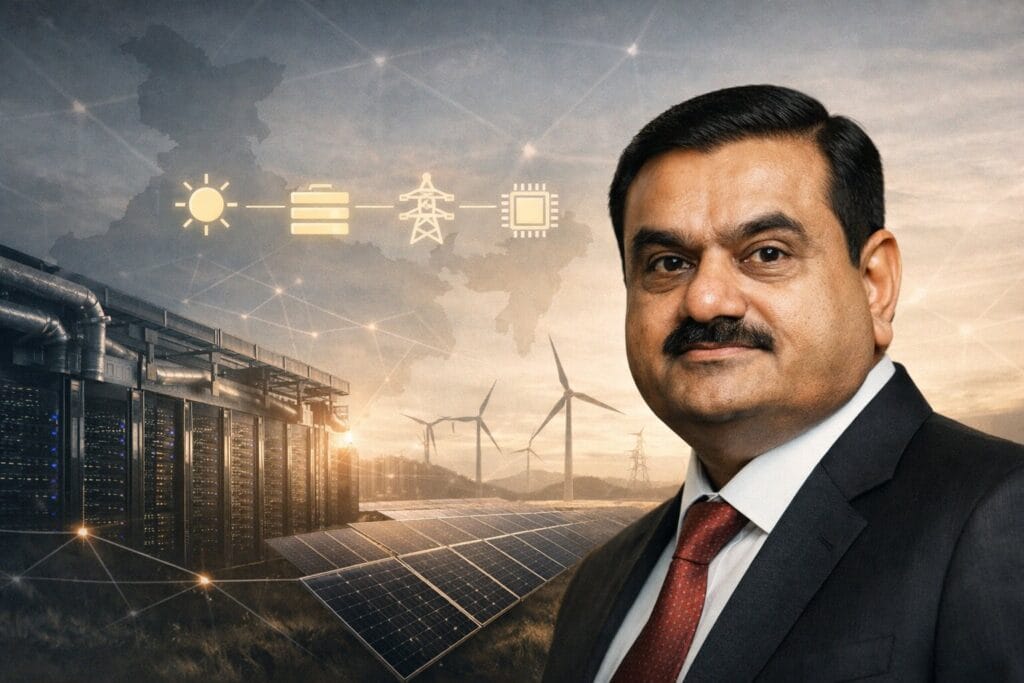

On February 17, 2026, India’s Adani Group said it will invest $100 billion by 2035 to build renewable-energy-powered, hyperscale “AI-ready” data centres — and, crucially, to build them as an integrated energy-and-compute platform rather than a string of standalone server farms.

If that sounds like corporate ambition-speak, look at the unit economics hiding in plain sight: electricity is rapidly becoming the binding constraint on AI. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects global data-centre electricity consumption reaches ~945 TWh by 2030, roughly doubling from today’s levels in its base case.

Adani’s announcement is a bet that India can compete in the “intelligence economy” by doing what it already knows how to do at industrial scale: build physical infrastructure — power generation, transmission, land, ports, cables, and now high-density compute — and stitch it together into something investors can finance and hyperscalers can trust.

The climate question is the real one: does “renewable-powered” mean clean electricity on paper, or clean electricity in the hour the GPUs are actually running?

Table of Contents

ToggleThe plan: scale AdaniConneX to 5 GW, then wrap it in renewables, grids and cooling

Adani says the roadmap will expand AdaniConneX’s existing 2 GW national data-centre platform toward a 5 GW target.

It also points to named partnerships and build sites:

- Google: a “gigawatt-scale” AI data-centre campus in Visakhapatnam (Andhra Pradesh), with additional campuses in Noida.

- Microsoft: projects spanning Hyderabad and Pune.

- Flipkart: an expanded partnership to develop a second AI data centre aimed at e-commerce and large AI workloads.

Adani frames the whole thing as “one of the world’s largest integrated energy-compute commitments,” projecting the $100B will catalyse another $150B across servers, manufacturing, and sovereign cloud — a $250B “AI infrastructure ecosystem.”

Under the hood, the release reads like a checklist of what hyperscale operators and grid planners fight about today:

- High-density clusters + liquid cooling for next-gen AI workloads

- Transmission and “grid resilience” built in parallel with compute

- Dedicated compute capacity for Indian large-language-model efforts and “national data initiatives,” with a portion of GPU capacity reserved for startups and research

- A pledge to co-invest in domestic manufacturing for transformers, power electronics, grid systems, inverters, and thermal management components

This is what the data-centre industry has been drifting toward: the power company and the compute company are converging — especially for AI-heavy workloads that need continuous, high-quality power.

How big is 5 GW, really?

“5 GW” is a power-system number — the language of generation fleets and transmission corridors — not a typical IT budget line.

To make it tangible, 5 gigawatts = 5,000 megawatts. If a platform ran at a continuous 5,000 MW draw for a full year:

- 5,000 MW × 24 hours/day × 365 days/year

- = 43,800,000 MWh/year

- = 43,800 GWh/year

- = 43.8 TWh/year

That’s only a back-of-the-envelope (real utilisation varies; total facility demand depends on cooling and power-conversion overhead). But it lands in the same universe as what analysts expect for India’s sector as a whole: S&P Global Commodity Insights estimates India’s data centres consumed about 13 TWh at end-2024 and could reach ~57 TWh by 2030 as the country adds more than 5 GW of additional IT load capacity.

In other words: Adani’s 5 GW target is not a “side bet.” It’s a direct play on what could become one of the most consequential new electricity demand blocks in India’s next decade.

“The wars that we have to fight today are often invisible. They are fought in server farms, and not in trenches. The weapons are algorithms, not guns. The empires are not built on land — they are built in data centres.”

Gautam Adani

Chairman, Adani Group

“Renewable-powered” has three meanings — and only one is climate-proof

Every data-centre developer now speaks the language of renewables. But “renewable-powered” can mean very different things in the real world:

- Annual matching (the easy version)

You buy renewable energy certificates or sign PPAs that add up to your annual usage. The grid still supplies you hour-to-hour, which can mean coal-heavy power during peaks. - Contracted clean supply + storage (the harder version)

You pair dedicated renewables with firming — batteries, demand response, and fast-ramping capacity — and design the campus around grid constraints. - 24/7 carbon-free energy (the hardest version)

You try to match clean generation to consumption every hour, which is both more climate-credible and more expensive, requiring a serious blend of storage, grid access, and dispatchable clean power.

Adani is clearly pointing toward versions (2) and (3) by emphasizing grid resilience, transmission buildout, and “one of the world’s largest” battery energy storage systems.

The company also positions its renewable backbone around Adani Green Energy’s 30 GW Khavda project, with over 10 GW already operational, plus an additional $55B committed to expand renewables and storage.

That matters because the IEA’s warning is implicit: as data-centre demand rises, delays in grid connections and clean buildout can push more supply toward fossil fuels. Across scenarios, renewables do most of the work — but in “lift-off” style growth, constraints can keep fossil generation in the mix longer than policymakers (or corporate ESG teams) would like.

So the climate integrity of Adani’s plan won’t be decided by a press release. It will be decided by hourly power flows, interconnection queues, and whether storage and transmission arrive on schedule.

India’s constraint set: spiky loads, coal-heavy grids, and water

The core challenge isn’t building data halls. It’s building them without breaking local grids — and without externalising costs onto communities.

Grid behaviour: Data centres don’t always behave like traditional industrial loads. India’s grid planners worry about sharp ramps and what one expert described as “silent exits” — sudden drops that complicate system balancing.

Generation mix: Many Indian data centres still rely on grid electricity dominated by conventional fuels and heavy coal. S&P notes coal-based power is more than 70% of total electricity generation (in its description of the current mix), and backup systems often include diesel generators and UPS/inverter systems.

Water: AI doesn’t just need electrons — it needs heat removal. Water availability is increasingly a limiting factor in major urban hubs like Mumbai, Bengaluru and Chennai, where many facilities cluster. S&P flags cooling water demand and cites an estimate of about 25.5 million liters per year for a 1 MW load (via Uptime Institute data referenced in the piece).

This is why Adani’s emphasis on advanced liquid cooling is notable — it’s a performance enabler, but also a resource and siting problem that policymakers are only beginning to price in.

The broader macro trend is clear: analysts expect India’s data-centre electricity demand share to rise sharply, from ~0.8% in 2024 to ~2.6% by 2030 in S&P’s estimate — and that’s before you layer in an AI acceleration scenario.

The strategic bet: build “sovereign AI” by owning the bottlenecks

Adani’s pitch leans into a politically resonant theme: data sovereignty plus industrial jobs.

The company says a “significant portion” of GPU capacity will be reserved for Indian startups and research institutions to relieve compute scarcity.

It also explicitly links the program to domestic manufacturing of power and thermal components — a nod to the reality that the global grid and cooling supply chain (transformers, switchgear, power electronics) has become a choke point across the world.

And, in a separate Adani release about its Google partnership, the company describes co-investment in new transmission lines, clean generation and energy storage designed not only to supply the campus, but also to improve grid resilience.

This is the thesis in one line: if you can deliver power, land, and interconnect reliably, you can become indispensable to the AI stack — even if you don’t manufacture chips. Reuters underscores the same logic, noting India’s limited chip manufacturing footprint and the view that data centres may be its most realistic route to AI scale near-term.

What to watch next (the “real-world” scorecard)

If you want to know whether this becomes a genuine ClimateTech inflection — or a branding exercise — watch for specifics in six areas:

- Hourly clean power claims

Do future disclosures move from “renewable-powered” to 24/7 matched procurement, or stay at annual accounting? - Storage size, duration, and siting

“Large BESS” is not a spec sheet. The climate value depends on duration (hours), interconnection, and whether storage is deployed where the grid is constrained. - Transmission buildout and queue strategy

AI campuses are often bottlenecked by grid interconnect and transmission. The Google partnership already points to transmission co-investment — expect more detail. - Water and heat

Where will liquid cooling be deployed, and how will campuses address water stress? The industry is moving fast here — but India’s water geography doesn’t forgive hand-waving. - Governance of “sovereign compute” allocation

If GPUs are “reserved” for startups and research, under what model — pricing, access, and transparency? - Timeline reality

Adani has stated a 2035 investment horizon; the interim milestones — MW brought online, PPAs signed, grid upgrades commissioned — will determine whether this is a decade-long execution story or a headline.

Bottom line

Adani is trying to do something bigger than building data centres: it’s trying to industrialise the link between electrons and intelligence — making renewables, storage, transmission and thermal management part of the AI product.

The upside is straightforward: if India’s next wave of compute comes with new clean generation and firming capacity, the country doesn’t just get AI infrastructure — it gets a faster energy transition. The downside is equally straightforward: if “renewable-powered” ends up meaning “renewables somewhere on the balance sheet,” India risks adding a giant new electricity load while remaining structurally dependent on coal-heavy grids and water-stressed cooling.

In the AI era, ClimateTech isn’t just building clean power. It’s proving that clean power can support always-on, high-density compute at scale. Adani just put a very large number on that proposition.