At a giant cement plant on the Gulf of Oman, five tonnes of CO₂ a day are being steered away from the atmosphere and into the ground. On its own, that number barely registers in a sector that emits more than a billion tonnes of CO₂ each year. But the way it is being done – by turning flue gas into stone inside a nearby mountain – points to where one corner of heavy industry might be headed.

Table of Contents

ToggleA small pipe into a very big problem

On 9 December 2025, Holcim and Omani carbon-removal start-up 44.01 announced what they describe as the world’s first pilot project to mineralise CO₂ captured at a cement plant. At Holcim’s 3.2-million-tonne-per-year cement works in Fujairah, flue gas from clinker production will be scrubbed, concentrated and then injected into underground rock, where it is expected to turn into stable mineral carbonates.

The numbers are modest. The pilot aims initially to capture around five tonnes of CO₂ per day – roughly 1,800 tonnes a year if it ran continuously.

By contrast, the global cement industry is responsible for about 7–8% of total CO₂ emissions, or around 1.6 billion tonnes in 2022 alone. And overall CO₂ from fossil fuels and cement reached another record in 2024, at about 37–38 billion tonnes, pushing atmospheric concentrations to roughly 422–423 parts per million – around 50% above pre-industrial levels.

Against that backdrop, a five-tonne-a-day pilot looks, at best, symbolic. Yet it is precisely these small, tightly engineered projects that will test whether “hard-to-abate” industries such as cement can move beyond incremental efficiency gains and into genuine deep decarbonisation.

Why cement refuses to behave

Cement has earned its hard-to-abate label the hard way. To make ordinary grey cement, producers heat a mixture of limestone and clay to more than 1,400°C in a kiln, driving off CO₂ from the limestone to create “clinker”, which is then ground and blended into cement.

Two problems follow:

- Process emissions. Even if the kiln were powered entirely by clean energy, the chemical reaction that turns calcium carbonate into calcium oxide releases CO₂.

- Fuel emissions. The high temperatures are still mostly delivered by burning fossil fuels, especially coal and petcoke.

On average, each tonne of grey cement today still generates around 0.6 tonnes of CO₂, with specific intensities in many markets ranging from 0.5 to 0.8 tonnes.

Because cement is used in almost every building, road and bridge, global demand is expected to remain high – and to grow in parts of the Global South. As a result, the sector sits behind only steel as an industrial emitter, accounting for roughly 7% of global emissions.

Over the past three decades, the industry has chipped away at that footprint. Members of the Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA) report a roughly 23–25% reduction in CO₂ per tonne of product since 1990, helped by efficiency gains, more alternative fuels and lower clinker-to-cement ratios.

But their own 2050 roadmap concedes that efficiency and fuel-switching will not be enough. To hit net-zero, the sector will have to combine demand-side measures and new binders with large-scale carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS).

That is where projects like Fujairah come in.

Holcim’s broader bet on carbon capture

Holcim, the Swiss-based building-materials group, has positioned itself as an early mover on cement decarbonisation. The company has committed to cutting its net emissions per tonne of cementitious material to below 400kg of CO₂ by 2030, aligned with a 1.5°C pathway, and to net-zero across its value chain by mid-century.

To get there, Holcim is pursuing a portfolio: more low-clinker products such as its ECOPlanet cements, more circular aggregates, and a network of more than 50 CCUS and mineralisation projects worldwide at various stages of development.

The Fujairah plant – previously known as Lafarge Emirates Cement – is an important node in that strategy. Located on the UAE’s east coast, it has an annual cement production capacity of about 3.2 million tonnes, serving both domestic and export markets.

Using a global average intensity of 0.6 tonnes of CO₂ per tonne of cement as a rough benchmark, a plant of that size could easily emit on the order of two million tonnes of CO₂ a year. Even allowing for Holcim UAE’s above-average performance – the company says it already uses over 40% alternative fuels at Fujairah and is installing waste-heat recovery to cut electricity demand by about a quarter – the site remains a large point source.

On that basis, a pilot capturing five tonnes a day would remove well under 1% of the plant’s current annual emissions, even if run around the clock. But Holcim and 44.01 are explicit that the point is not the tonnage today. It is about proving that cement-derived CO₂ can be fed into the same kind of mineralisation “sink” that 44.01 has been testing with other emitters.

How do you turn flue gas into stone?

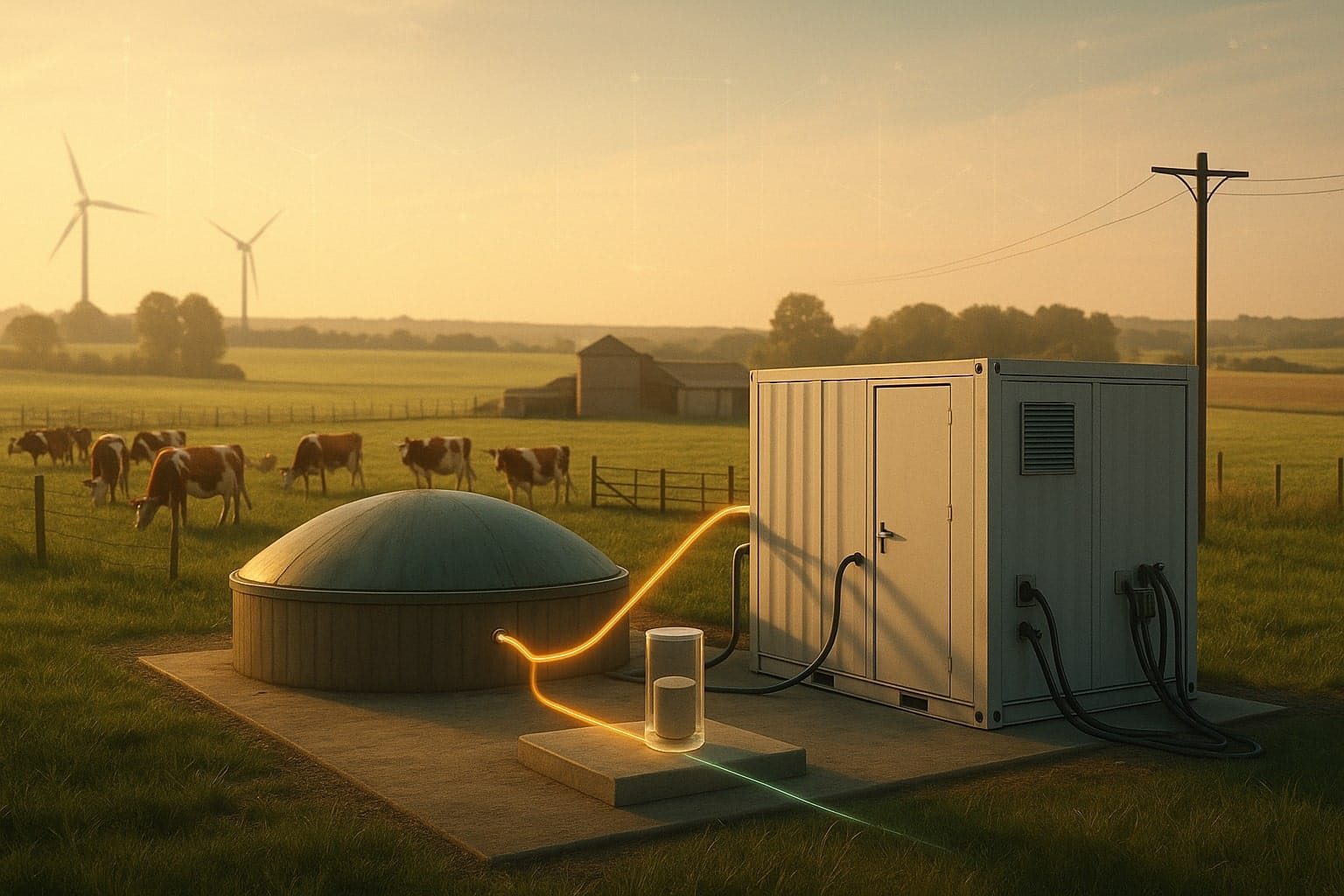

Carbon mineralisation is a natural process. Over geological timescales, CO₂ dissolved in water reacts with rocks rich in magnesium, calcium and iron – such as peridotite or basalt – to form solid carbonate minerals.

44.01’s technology accelerates that process. According to the company’s own description, it:

- Takes CO₂ captured either from industrial flue gas or from the air and dissolves it in water – often seawater or treated wastewater – to create a carbonated injection fluid.

- Injects that fluid deep underground into reactive rocks, at depths below freshwater aquifers. Because the fluid is denser than freshwater, it tends to sink rather than rise.

- Allows the CO₂-bearing water to react with the host rock, forming stable carbonates in less than a year, monitored with geochemical and geophysical tools.

At Fujairah, the key rock is peridotite, an ultramafic rock unusually rich in magnesium and iron. The emirate sits atop substantial peridotite formations, which is one reason both ADNOC and 44.01 selected it for earlier mineralisation pilots.

The new Holcim-44.01 project brings an additional ingredient: a cement plant flue-gas stream. Instead of capturing CO₂ from the ambient air, Holcim will use Shell’s CANSOLV amine-based system, deployed by NT Energies, a joint venture between Technip Energies and NMDC Energy, to scrub CO₂ directly from the plant’s process gas.

The CO₂ is then passed to 44.01, dissolved in water and injected into peridotite under the supervision of the Fujairah Natural Resources Corporation and the emirate’s environment authority.

From a climate perspective, the crucial claim is not only that the CO₂ is stored, but that it is effectively eliminated. Once converted into carbonate minerals, the gas cannot migrate back into the atmosphere – unlike some conventional geological storage, which relies on keeping supercritical CO₂ trapped under caprock over centuries.

Fujairah’s earlier experiment: from air to rock

The Holcim pilot is not 44.01’s first encounter with Fujairah’s geology.

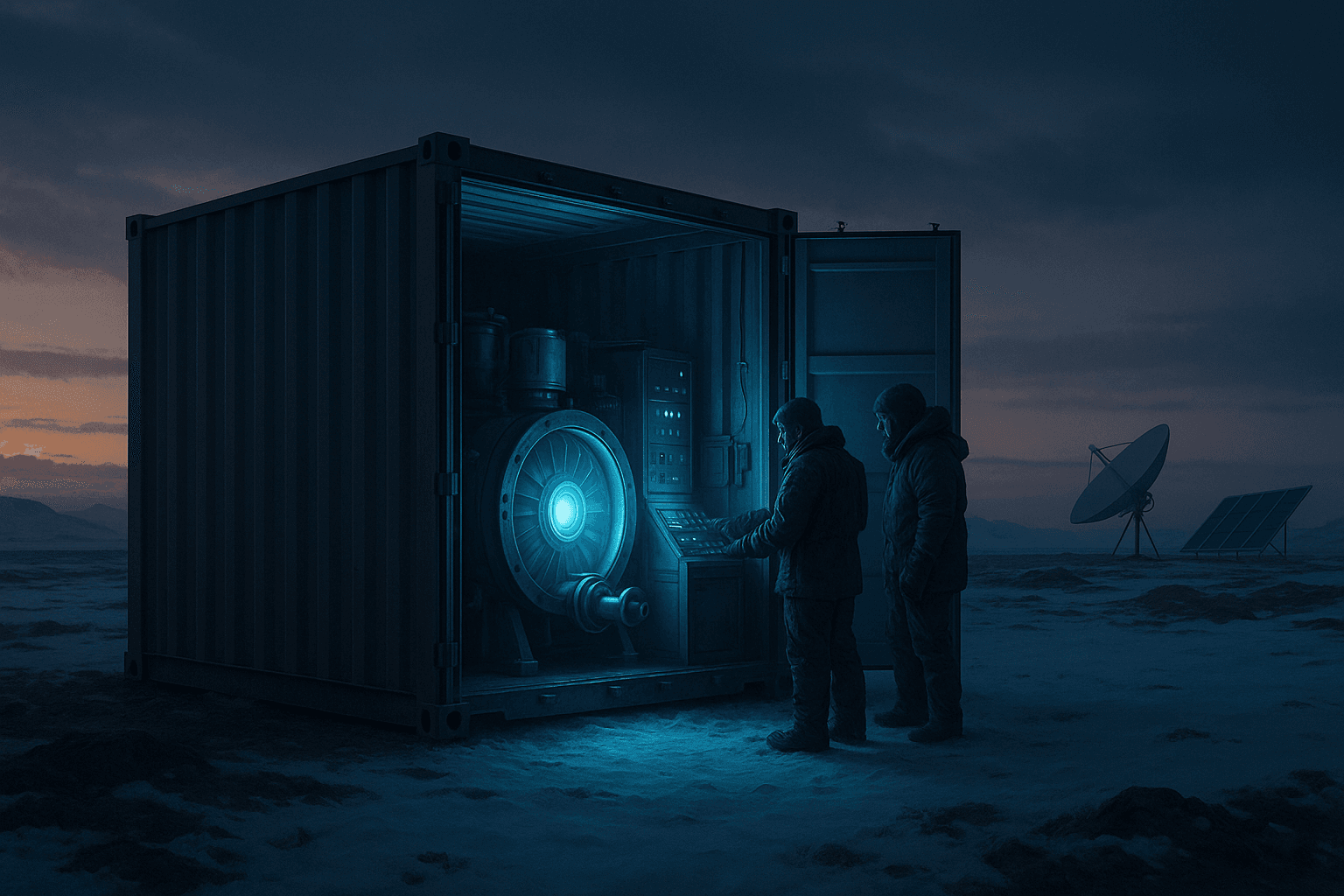

In 2023, the company – backed by ADNOC, Masdar and FNRC – began operating what it described as the UAE’s first mineralisation project in the emirate. That pilot captured CO₂ from the air via a direct air capture unit, mixed it with seawater and injected it into peridotite formations deep underground.

According to ADNOC, that initial phase mineralised about 10 tonnes of CO₂ in less than 100 days. Building on those results, the partners have now committed to a first scale-up phase that will inject more than 300 tonnes at the same Fujairah site.

The Fujairah pilot forms part of ADNOC’s wider carbon-management plan, which targets 10 million tonnes per year of carbon-capture capacity by 2030 as the company seeks to maintain oil and gas production while cutting its operational footprint.

For 44.01, these projects also demonstrate speed. A recent technical case study of peridotite mineralisation in Oman – a process similar to the one it uses – suggests that around 88% of injected CO₂ can mineralise in under two months under the right conditions.

The Holcim pilot effectively plugs a new source of CO₂ into this mineralisation “sink”. Instead of relying on relatively expensive direct air capture, it tests whether peridotite can also absorb emissions from existing industrial stacks – and whether the economics look any better when tied to a real plant with real customers.

How does this compare to “classic” CCS?

Carbon mineralisation is not the only route for cement producers.

In Norway, Heidelberg Materials’ Brevik plant has become a flagship for conventional carbon capture and storage. The facility, part of the government-backed Longship programme, is designed to capture around 400,000 tonnes of CO₂ per year – about half the plant’s emissions – from a cement line with a little over one million tonnes of annual capacity. The captured CO₂ is liquefied and shipped to the Northern Lights storage project in the North Sea, operated by Shell, Equinor and TotalEnergies.

On the demand side, Heidelberg says it has pre-sold all of the 2025 production of “evoZero”, its net-zero cement from the Brevik line, despite premium pricing and heavy public subsidy: Norway is covering roughly two-thirds of Longship’s estimated $3bn cost.

Compared with that, Holcim’s Fujairah pilot is tiny. But it explores a distinct storage pathway with several potential advantages:

- Permanence. Mineralisation converts CO₂ into rock, eliminating the risk of leakage that can complicate long-term monitoring and liability for conventional storage.

- Geological flexibility. Peridotite and similar ultramafic rocks occur on every continent, not just in offshore reservoirs accessible to CO₂ shipping.

- Modularity. Mineralisation projects can, in principle, start small and expand once a site’s capacity and chemistry are better understood.

They also pose new questions. Injecting carbonated water into rocks requires careful water management and geochemical monitoring. The economics depend not only on capture costs but on drilling, characterising and operating injection wells – areas where 44.01 is drawing heavily on the Middle East’s oil-and-gas service ecosystem.

And while mineralisation may be cheaper than large offshore storage hubs in some settings, there is not yet a robust public price signal for this specific kind of permanent storage, especially when tied to hard-to-abate industrial sources.

Does five tonnes a day matter?

On simple arithmetic, no. Even if Fujairah’s pilot runs smoothly, captures five tonnes of CO₂ every day and locks it into rock in under a year, it will address only a thin sliver of the plant’s emissions.

But the cement sector’s challenge is not just volume; it is variety. No single technology – not low-clinker cements, not alternative fuels, not carbon capture – can comfortably deliver a 90-plus per cent emissions cut on its own.

Seen in that light, projects such as Fujairah have three roles:

- Proof of integration. They show that point-source capture and mineralisation can be integrated into an operating cement plant, alongside other decarbonisation measures such as alternative fuels and waste-heat recovery.

- Learning and regulation. They give regulators, such as the Fujairah Environment Authority, a live case to work through permitting, monitoring and liability frameworks for permanent mineral storage tied to industry.

- Signalling and finance. They send a signal to investors and policymakers that mineralisation is no longer confined to remote pilot wells or DAC projects, but is starting to touch mainstream heavy assets.

If Holcim and 44.01 can demonstrate safe, verifiable mineralisation from a cement stack at Fujairah, the obvious next question will be one of scale.

44.01’s own ambitions are not modest: the company, which won the Earthshot Prize in 2022, has said it aims to mineralise one billion tonnes of CO₂ by 2040, leveraging peridotite formations in Oman, the UAE and beyond.

By comparison, cement alone emits more than that every single year.

Accounting for rock: removal, reduction or both?

One unresolved issue is how to account for the climate value of projects like Fujairah.

When 44.01 dissolves air-captured CO₂ in seawater and injects it into peridotite, the result is clearly a carbon removal: CO₂ that was in the atmosphere is now in rock. That is the use case that has attracted support from buyers of “durable removals” in voluntary carbon markets and from competitions such as XPRIZE Carbon Removal.

When the CO₂ comes from a cement stack, however, the boundaries blur. If a plant that would otherwise emit CO₂ captures and mineralises it instead, the primary benefit is an emissions reduction at source. But if the capture rate exceeds what is needed to neutralise the plant’s own footprint, additional tonnes might qualify as removals.

That distinction matters for carbon-crediting, regulation and public trust. The risk is that the same mineralised tonne could be counted once as avoided emissions for Holcim’s decarbonisation targets and again as a removal sold to a third-party buyer.

44.01 says it is investing in measurement, monitoring, reporting and verification (MMRV), reflecting the sector’s broader push for more rigorous accounting of engineered carbon-dioxide removal. But the frameworks that will decide how cement-plus-mineralisation is treated – in national inventories, emerging carbon-removal standards and future “carbon clubs” – are still evolving.

MENA’s peridotite moment

It is not an accident that this experiment is happening in the Gulf.

The United Arab Emirates has set a 2050 net-zero target, and has positioned itself as a hub for both renewable energy and carbon-capture projects, including ADNOC’s planned 10-million-tonne CCUS programme.

The region also has geology that naturally suits mineralisation. Oman hosts some of the world’s largest exposed peridotite formations, and Fujairah’s own rocks offer similar chemistry.

For governments seeking a post-hydrocarbon industrial strategy, this combination of geology, existing drilling expertise and state-backed heavy industry is attractive. Mineralisation projects promise not only climate benefits but also an opportunity to reuse skills and infrastructure from the oil-and-gas era.

Holcim’s Fujairah pilot sits neatly at that intersection: a European multinational experimenting with a Middle Eastern carbon-removal start-up, under the eye of a local regulator that controls the rocks beneath.

If it works – technically, commercially and politically – the model could be exported to other peridotite-rich regions, from parts of the US and Europe to Asia and Australasia.

Necessary, but nowhere near sufficient

None of this makes carbon mineralisation a silver bullet.

Even optimistic assessments of peridotite and basalt suggest that trillions of tonnes of CO₂ could be mineralised globally, but getting anywhere close to those numbers would require thousands of projects, billions of dollars of investment and robust social licence.

For cement producers, mineralisation – whether via projects like Fujairah or via basalt-based schemes such as Iceland’s Carbfix – will likely sit alongside a wider package:

- Less clinker-intensive products, including cements blended with alternative binders and recycled concrete fines.

- Demand-side changes, from longer-lived buildings to more efficient structural design.

- More renewable power and alternative fuels in kilns and grinding operations.

The real question is not whether five tonnes a day in Fujairah will move the global needle. It plainly will not. The question is whether these early-stage projects can prove out a new category of infrastructure that lets heavy emitters in favourable geologies move beyond offset-buying and into genuine, permanent CO₂ elimination.

Holcim’s pilot with 44.01 is one of the first attempts to hook a mainstream cement plant directly into such a system. If it delivers what its backers promise, the pipe running from Fujairah’s kiln stack into the rocks beneath the emirate may come to be seen not as a curiosity, but as one strand of a much larger web of pipes, wells and mineral formations that gradually shrinks the space available to industrial CO₂.

For now, it is still just a small stream of gas disappearing into the ground – and a test of whether turning cement’s emissions into stone can be part of building a low-carbon future, rather than a footnote in a world that failed to act in time.